Chad Ramey's rise, the course that groomed him, and the community that shaped him

Meet the only PGA Tour pro that practices at a nine-hole track with no driving range

Nestled adjacent to a patch of trees just to the right of the third hole at Fulton Country Club, Chad Ramey toweled off a mud-caked wedge and continued his work.

The thick, steamy air from a summer shower that had just passed through the area on this late June afternoon added to the ferociousness of the already sweltering Mississippi heat. Ramey hammered wedge after wedge. Golf balls spilled out of a Taylormade range bag that sat sideways on the ground. Some balls were eggshell white, an indicator of their age and the thousands of times they had been compressed. A Trackman monitor rested a few feet behind a slew of perfectly carved divots — the kind that serve as a subtle territory marker of a professional.

This picture looks like the stomping grounds of an overzealous scratch golfer who won’t let go of a dream and fully accept his fate as a weekend warrior. What you probably wouldn’t mistake this scene for is the training grounds for a newly-minted PGA Tour player, two days removed from the greatest triumph of his professional life and in the midst of one of the most dominant and consistent 18-month stretches of play that you’ll see in the profession.

The date was June 29 and Ramey was less than 48 hours removed from standing on the 18th green Falmouth Country Club in Falmouth, Maine — the site of his first professional win at the Korn Ferry Tour’s Live and Work in Maine Open. Ramey nursed a one-shot lead after 54 holes. A bogey-free 68 on Sunday sealed the deal as Ramey held off his closest friend on tour, Ryan Creel, for a one-stroke win. It was the icing on the cake to culminate an already life-changing seven days. Ramey locked up his 2021-22 PGA Tour Card the week prior after a T-13 finish at the Wichita Open, which pushed him beyond the fail-safe points threshold in the Korn Ferry standings, meaning he was guaranteed to remain in the top 25 for the rest of the season no matter how he played.

If you’re new here, in an effort to spare you from unpacking the incredibly confusing matrix that is golf’s minor league qualifying structure, let’s explain this simply: the Korn Ferry Tour is like Triple-A Baseball. It’s arguably the second-best tour on the planet (if you’re thinking ‘what about the European or Asian Tour?’ compare the depth of the fields of the three tours on any given week and get back to me). The top 25 in the points standings at the end of the Korn Ferry Tour season are awarded PGA Tour membership. After some changes to the PGA Tour’s qualifying school structure a few years ago, the Korn Ferry Tour is quite literally the only feasible path to making it to the PGA Tour. And make no mistake about it, the Korn Ferry Tour is a mental and physical grind. The way most tournaments are set up, par is not your friend. Two of the next three events after the stop in Maine were won with scores of 27-under par over four days. In other words, you better make a lot of birdies and bring it every single day for four days.

You don’t take weeks off on the Korn Ferry Tour. You simply can’t afford to. You’ll lose too much ground and waste opportunity that’s already scarce. Even winning a tournament doesn’t guarantee you’ll remain inside the top 25 at the end of the season.

“It is a physical and mental grind and you cannot let up,” Ramey said. “You just can’t. Because as soon as you do, someone is going to slip past you. It is a mental marathon really. You’ll have times where you will have bad thoughts in your head and you just have to get them out, get the mind refocused and get back to work.”

There’s no breathing room, which makes what Ramey has accomplished over these last 19 months so remarkable. He secured his PGA Tour card on the second-best tour on earth without winning a tournament. Not impressed yet? What if I told you the COVID-19 pandemic forced the Korn Ferry Tour to have a wraparound season, which essentially means two seasons counted as one. What happens if you were inside the top 25 at the culmination of the 2020 portion of the schedule? Well, tough shit, do it again in 2021.

How’d he do it? Oh, just by casually making 37 of 40 cuts with 10 top-10 finishes and four top-5 finishes. Ramey made 23 consecutive cuts to end the season. The last time he didn’t see the weekend at an event he played, the previous Presidential administration still had five more months left in office. He’s missed one cut since February 9, 2020. Anyone who has ever picked up a golf club would kill for that level of consistency.

So, what's Ramey’s secret? How has this quiet, unassuming 28-year-old from Fulton, Mississippi, pieced together this run that’s propelled him to the highest level of the sport? The answer to that question is as improbable as it is fitting, and it all began on the very patch of grass beneath his feet on this sweltering afternoon in late June in the heart of Fulton Country Club.

Clad in a grey Mississippi State t-shirt, gym shorts, a backward black Taylormade hat and a pair of Nike shoes, sweat dripping down his face, Ramey is in his element, grinding just like he has since he was a young child. But his home turf is drastically different from any other PGA Tour player's practice grounds. Fulton Country Club is a nine-hole golf course in rural North Mississippi. It has no driving range. Yes, seriously.

“It’s where I grew up,” Ramey said. “I’m comfortable here.”

Ramey works in an industry comprised of men that seek out a competitive advantage on an almost obsessive level. Most Tour players move to Florida or some other paradise-like area, where sprawling luxury golf properties stretch as far as the eye can see with indoor and outdoor hitting bays, cutting edge technology and an abundance of other amenities to aid the team of coaches molding elite talents into the best version of themselves. That’s just not really Ramey’s style. His father, Stanley, is the superintendent at Fulton and the Ramey family house sits on the course. Chad lives in his childhood home. Stanley is Chad’s unofficial coach. The two work together on his swing and his game as a whole. The pair has always strived for consistency that will withstand the toughest tests. In their humble utopia just outside of Tupelo, they’ve achieved that and more.

"That is one of the things my dad and I have tried to emphasize is to live by the consistency aspect of it,” Chad said. “Let’s try to get every part of my game as consistent as possible.”

At the risk of making Chad sound like a real-life Tin Cup, he does have more firepower in the holster when he needs it. Fulton is an hour away from West Point, home to Old Waverly and Mossy Oak Golf Club, which are two of the best courses and most pristine facilities in the southeast. Chad has been coached by V.J. Trolio and Tim Yelverton since he was a kid. Trolio has been named a top 100 instructor by Golf Digest and Yelverton is one of the finest short game specialists in the country. But by Ramey’s own admission, he spends about 80 percent of his down time at Fulton CC.

“He’d go to lessons with V.J. and Tim and then we’d come back and do our own little thing,” Stanley said. “We called it ‘rednecking it up’ and figured it out that way.”

Underestimate Chad, Stanley and Fulton at your own risk. It’s home to two professionals. Chad grew up playing with Ally McDonald Ewing, a two-time winner on the LPGA Tour and the 17th-ranked player in the world. Stanley has caddied for Ewing on numerous occasions and had a front-row seat to watch the two transform into the stars they’ve become today.

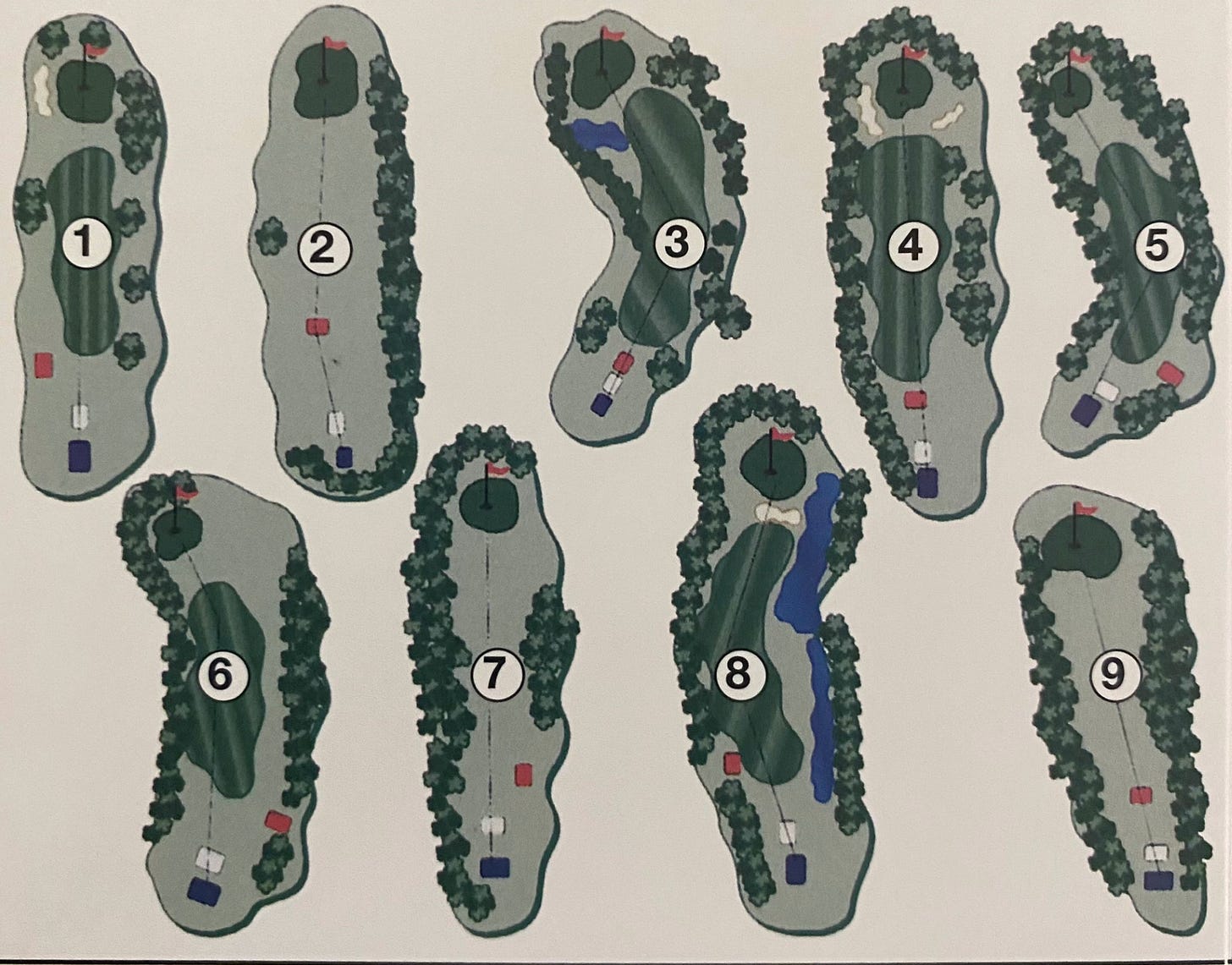

Chad and Ally crushed tens of thousands of golf balls together, on this very same plot of grass he stands on, two days removed from his first professional win, resting between holes No. 2 and 3 at Fulton Country Club. Ramey hits 30-100 yard wedges to the various tee boxes on hole No.1. If he wants to dial in his irons, he turns slightly to the right and pounds them down to a landing area roughly 60-70 yards short of No. 1 green, where most members cannot reach with their tee shot and don’t land in barring a catastrophic approach shot.

“I have known the people and the members my whole life,” Chad said. “Everyone is okay with it. They know I play for a living. I just try to stay out of the way as best I can.”

When he works on woods and the driver, he simply hops on a vacant hole and hammers away. There isn't much of a short game and putting area at Fulton, and the greens roll about a six on the stimpmeter, which is basically unrecognizable to anything he’ll ever play in a professional setting.

“I’ve never really had a problem going from slow greens to fast greens though,” Chad retorted.

If you’re bewildered at the notion of a professional golfer practicing in a setting like this, you’re missing the point. These trees, these greens, this patch of grass and this quaint nine-hole track made Chad Ramey who he is today and helped fuel his rise. Stanley has tended to this property for over two decades. His father nurtured the course before that.

Perhaps above all else, the people of Fulton helped push Ramey to where he stands today as an incoming rookie on the PGA Tour.

Professional golf is an incredibly expensive dream to pursue. Money is both what fuels the chase and often brings it to a premature end. The elite college players sign with agencies and court sponsors more quickly than the others. For everyone else, funding can be a little bit more difficult to come by. Fulton Country Club has just over 200 members. When Chad turned pro, ten members put up $5,000 apiece to get Chad up $50,000 to start his career. This helped pay for entry fees, travel and other expenses.

"We're a laid back club, a small club," Stanley said. "Everyone takes care of each other around here. We are so incredibly appreciative of them helping Chad."

One indisputable fact about Chad Ramey’s rise in professional golf is that nothing has been handed to him. He started where most aspiring professionals do: on the mini tours. It is an adventurous life, to say the least.

“It’s basically legalized gambling,” Chad said. “You put up $1,500 to win $10,000-12,000.”

Though a win never came, he kept making cuts. More importantly, he wasn’t losing money. The remarkable consistency Ramey has shown is what every golfer in the sport vies for. It bears repeating: August 23rd, 2020 is the last time Ramey entered an event in which he didn’t see the weekend. That’s an astounding feat.

This incredible run, particularly before his breakthrough win in Maine, encapsulates his rise, but in a way, also underscores why he’s always flown under the radar for most of his junior, amateur and professional career. Consistency is what keeps you afloat. Winning gets you noticed. Ramey’s win in Maine was only the second victory of any kind since high school. He won once in his collegiate career at Mississippi State, amid a slew of top-10 finishes, school records and First-Team All-SEC honor recognition.

Still, he seemed to fly under the radar. In 2018, Chad Monday qualified for his home state’s PGA Tour event, the Sanderson Farms Championship, and finished T-25 for his first made cut on the PGA Tour. The next year, he tried to get a sponsor’s exemption and seemed like a lock — a Mississippi kid with decent status on the Korn Ferry Tour and seemingly close to a breakthrough. He wasn’t awarded one.

“I feel like it might have helped in the long run,” Chad said. “It made me feel like I had to earn it, so maybe it helped with the mindset. If I want something, I have to go get it. Nothing in life is going to be given to me.”

Undeterred, Ramey made it through qualifying school again and finished 34th in the Korn Ferry season points standings in 2019, which granted him full status on that tour for the 2020 season. More importantly, he had newfound security, a rarity in the lower levels of professional golf. This meant he didn’t have to go back to qualifying school and for the first time in his career, he had an offseason to rest and practice.

He spent most of the fall and winter where he’s most comfortable: nestled in the middle of the nine holes that taught him the game he turned into a profession, surrounded by a trackman and a bag of golf balls he’ll shag himself when empty. He hammered wedge-after-wedge to various tee boxes.

“He would honestly rather be here because he doesn’t draw much attention. He can go off by himself into his own little world here," Stanley said. "He can do wonders scooping up balls with a wedge. It's a character builder, I like to think."

Ramey missed two of his first four cuts to start the 2020 season. He registered a T-2 finish at the event in Mexico to kickstart his season. The season was suspended six days later as the COVID-19 pandemic forced the entire globe to grind to a halt. He wouldn’t tee it up again in competition until mid-June. Ramey returned home to Fulton and worked on his game. With the world shut down, there was quite literally nothing else to do but play golf. Ramey is quick to point out that the pandemic didn't alter his lifestyle drastically. He practiced, ate, slept and repeated -- all at the heart of his comfort zone. This is where a lightbulb moment led to a change in practice philosophy that took Ramey's game to another level.

In a Q/A written by Will Bardwell on his Lying Four website last winter, Ramey talked at length about spending 80 percent of his practice time during the shutdown on his wedges and short game -- the type of practice most conducive to his setup at Fulton. Consistency is his philosophy. It's similar to what he works on with his coaches at Old Waverly and with Stanley. His motion on a pitch shot is shorter, but not that dissimilar to his driver action. Once the Korn Ferry Tour restarted, the results came and the philosophy proved to be fruitful.

He made the cut in each of the first 10 events back, including a solo 3rd, 6th and T-2 finish. After that missed cut in late August, he finished off the year with a T-3 and 4th place finish. In a normal year, he would've earned his PGA Tour card and moved on to golf's biggest stage, but the pandemic presented a truly unprecedented set of circumstances, and it meant Ramey had more work to do to realize his dream.

“It is obviously not something I wanted to happen," Chad said. "But It was just something that was completely out of my control and the mindset I had was just keep grinding, keep my foot on the gas and work for every single point..

"I do realize some of the things that I have done, but I just feel like that in this profession, as soon as you take a step back to realize what you have done, bad things can happen. You have to keep looking forward.”

Ramey registered two top-10 finishes in the first four events of the 2021 portion of the schedule. He was inching toward becoming a lock to earn a PGA Tour Card. But that's the thing with this grueling tour, the minute you relax, someone passes you by. One Korn Ferry season is difficult enough, then there's remaining in the top 25 for the equivalent of two seasons. Being 30 events and 18 months into a marathon of a season without the guarantee of a PGA Tour card can be demoralizing, no matter how likely it may seem.

By June 15th, Ramey had notched nine top-10 results but was still searching for his first professional win. A week later, that T-13 finish in Wichita cemented things. Ramey officially locked up his 2021-22 PGA Tour card.

The next event was in Maine, a stop on the schedule his family and a few close friends already planned to attend as a mini-vacation while getting the chance to watch him play. His caddie asked for the week off and Stanley filled in for the week. Stanley and his wife, Trish, had some travel issues that forced him to miss both practice rounds. Chad’s fiancé, Kelly, caddied until Stanley arrived the night before the tournament, having never seen the course.

“We pulled it up on Google Earth,” Stanley said. “You can do wonders with that thing.”

The duo opened with a 67. A scorching back-nine 30 on Friday helped Ramey card a 65 and put him in contention. He sat on the 54-hole lead after three days -- 18 holes away from the biggest win of his life. He turned at 2-under on Sunday and nursed a one-shot lead with nine holes to play.

“I was just trying to stay level-headed," Chad said. "In all of those second and third-place finishes, I had bits and pieces in moments of having what it takes. I knew it was there. I just needed to do it for four rounds instead of three. It’s the mentality of knowing it is there and stretching it out for four rounds."

Once Creel birdied the 17th hole a few groups ahead to trim Ramey's lead to one, he needed a par at the last to seal the win. He hit the fairway, put one on the green and two-putted for the win. Already having realized a dream, Ramey now had the experience of being in the arena, late on a Sunday afternoon and coming out on top. His mom, fiancée and friends rushed onto the 18th green to greet him as the emotions poured out.

“I have always thought I could do it, but I proved it that week," Chad said. "I now have that added confidence that I can do it, because I actually have done it.”

Maybe this was all fitting. The pressure, the waiting, the countless close calls, the marathon of a season amid unprecedented circumstances and the people on hand to watch him finally leave with a trophy. Maybe it was fitting that his first win came with his father -- the man that introduced him to the game, still coaches him and maintains the course he grew up on -- on the bag and by his side from start to finish. Maybe it was fitting that a guy who perpetually flies under the radar, despite his last two years being a model of consistency, broke through in his 36th event of the year. Fitting that a guy who's been handed nothing in professional golf realized his PGA Tour dream by being almost robotically consistent without a win. And maybe it was fitting it came with the people closest to him in attendance, over 1,400 miles away from home.

It's fitting that less than 48 hours after the greatest day of his professional life, Chad Ramey was back where he's most comfortable: adjacent to that patch of trees just off the third hole of Fulton Country Club, pelting golf balls into the sky, on the same grass and around the same people that built him for stardom.